“Heretic!”

That’s what someone shouted out at the midway point of my sermon just six days after the inauguration. It was not the kind of call and response I was hoping for.

Our congregation is journeying through the Sermon on the Mount for the first three months of 2025. I was up to Jesus’s seventh and eighth beatitude,

“blessed are the peacemakers for they will be called children of God. Blessed are those who are persecuted for righteousness for theirs is the kingdom of heaven.”

It was at this point where I made a brief comment about the recent viral exchange between Bishop Mariann Budde and President Trump.

Bishop Budde, at the inaugural prayer service, made a plea to President Trump to show mercy to those who living in fear because of their immigration status and sexual identity. While many saw this as a political stunt, I heard her words as a pastoral invitation to the most powerful person in the world (as we define power from a worldly perspective) to create conditions of good-will through his leadership.

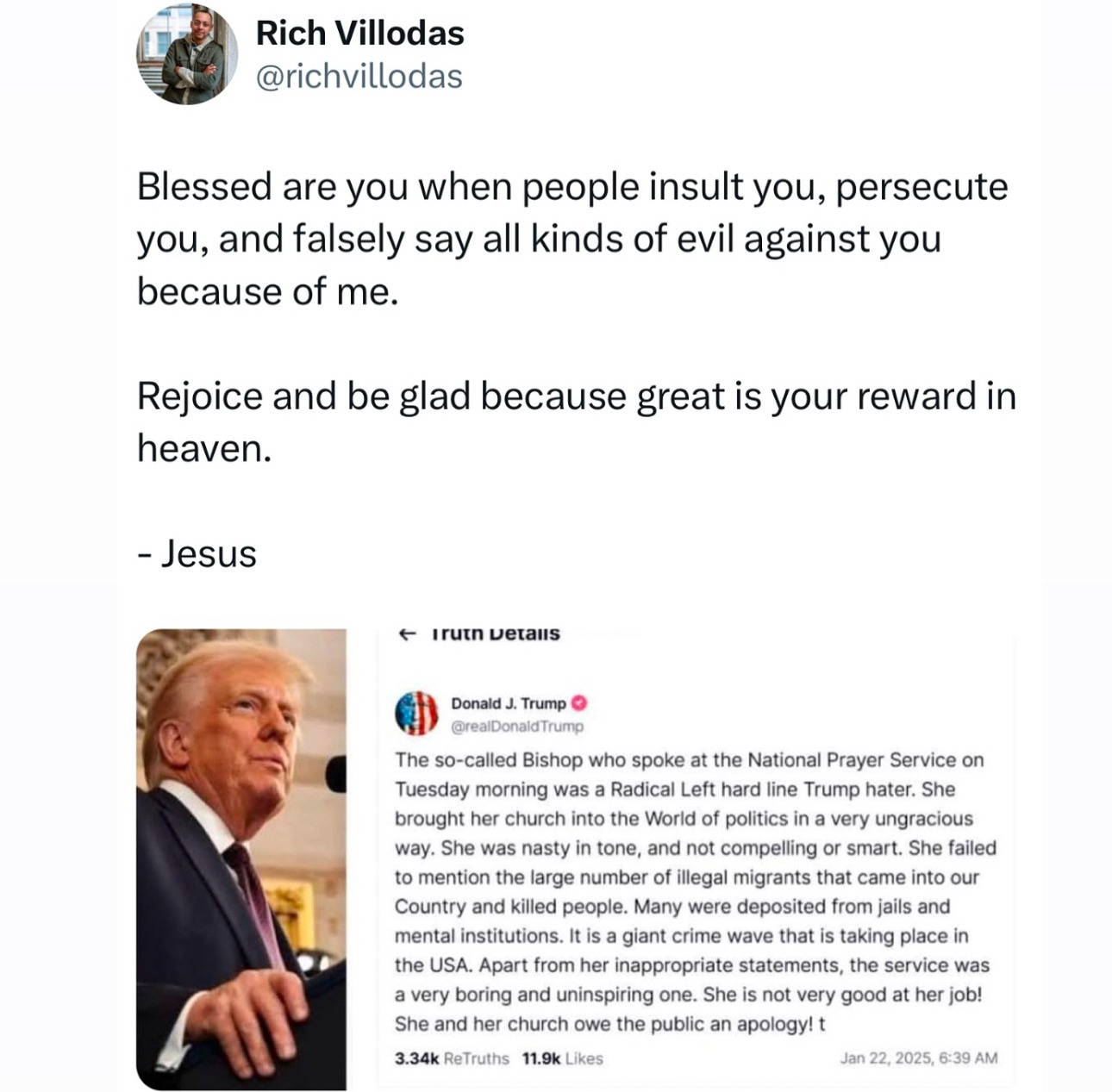

This plea was met by a swift response from Mr. Trump calling her tone “nasty.” He would also say she was “not compelling or smart.”

The sermon, and the president’s social media response, caused a great stir.

In my sermon, I mentioned that making peace comes with a warning: peacemaking can lead to persecution. Peacemaking can be a dangerous act.

I briefly made mention of the recent kerfuffle surrounding the inaugural service, and noted that a call for mercy reflected the heart of the beatitudes.

There was a moment of silence and then came the voice of someone saying “heretic!” It wasn’t initially clear to me in the moment that he was directing his ire against Bishop Budde, but hearing that word, nonetheless made for a tense moment.

I continued my sermon, appealing to the congregation to be peacemakers. I noted that a peacemaker is someone who at times disrupts false peace but works hard to resist disconnection. The service ended and I went to the lobby as I do every Sunday to greet congregants. The man who shouted lingered for a moment and approached me.

I shook his hand and he voluntarily shared that he was the one who shouted during my sermon. He spoke with kindness in his voice––something I didn’t anticipate––and wore concern on his face. I asked him to share why he shouted out during the message.

He had three reasons: first, he was disappointed that I didn’t include President’s Trump’s peacemaking efforts to stop the war between Russia and Ukraine. Second, as someone who has immigrated to the United States and became a citizen, he was upset that undocumented immigrants are breaking the law. (In fact, many commented to me on social media that a call for mercy effectively means the eradication of the rule of law in this context.)

And finally, because of Bishop Budde’s stance of various theological matters––particularly human sexuality––he regarded her words as heretical, no matter how biblical they sounded.

The conversation lasted about four minutes. It was surprisingly cordial. While speaking, I would place my hand on his shoulder offering my perspective. He was warm, but bothered. I discovered that he had been attending our church for about three months. The conversation ended, he left, and I went to preach again at the next service.

In many ways, my exchange with this brother was a moment of peacemaking. At the same time, it revealed a number of insights into the fractures that exist within and without the church.

Since that inaugural prayer service, I’ve been reflecting on why it caused the stir it did. On social media, I made a brief comment appealing to the beatitudes and why Jesus’s words should set the tone for our public engagement. I also referred to Jesus’s eight beatitude in response to President Trump’s social media post.

This led to a number of passionate, and at times, angry comments. In the process, a number of observations became clear once again. Here are a few of them. (And truth be told, I’m able to name these in large part because they live within me.)

Offering a different opinion on a significant matter often reveals the fear, anger, and reactivity people live with daily.

Our sense of “okayness” is often derived from the absence of resistance to values or opinions that we carry. Depending on the nature of the value, we are easily emotionally triggered when there’s a difference of opinion. Certainly, values matter. But the immediacy by which we express anger and fear expresses the ways we live from a place of reactivity and not reflection.

Political enmeshment is a very real issue. To offer critique around a political personality or a political position is internalized and personalized. In other words, to express concern about a political matter is taken as a pointed shot at “me.”

Enmeshment is our tendency to “fuse” with others in such a way that it becomes hard to determine where one person ends and another begins. We see this in parent-child relationships, marriages, churches and friendships.

We also see it in the world of politics. In an ever-increasing way, people are so enmeshed with political figures and parties that it’s hard to distinguish themselves from it. This reality is especially revealed when criticism surfaces. As a pastor, I’m keen to understand the deep emotional movements that bonds or repels us from one another.

How do we understand the resistance many have to critique one’s own party? How do we grasp the anxiety people carry when their candidate is under fire? In short, by unraveling the domino effect of enmeshment. This is deep work. For people of faith in particular, this domino effect looks something like this:

To critique a political leader it to critique the party I align with.

To critique the party is to critique the values I hold dear.

To critique the values I hold dear is to critique my vision of a flourishing world.

To critique my vision of a flourishing world is to critique my understanding of God.

To critique my understanding of God is to critique me at my deepest center.

When seen in this way, it makes sense why people get defensive when their political leader is criticized.

But this is an alarming reality. One of the reasons for the intensified hostility is that many have not been able to see themselves apart from the larger political movements, personalities and platforms they support. This is not a call for rampant individualism. Rather, it’s a call to live free from the all-encompassing need to have one’s identity validated by political power.

The pathway to greater civility, collaboration and healing is found in our emotional health; our commitment to interiority. Minimally, this speaks to a commitment to separate ourselves from disordered attachments. For people of faith, this is the ancient call to reject idolatry. Idolatry is the unquestioned allegiance one gives to something, or someone other than God. This rejection is not just practiced through theological commitment, but by emotional clarity.

Until we are emotionally present with ourselves, naming the enmeshment we are prone to be entangled in, we will take critique of our affiliations as outright criticisms of who we are at our deepest center.

So then, when the candidate or party, or position you support is criticized, and you feel deep anger and defensiveness, the question we need to ask is:

Why am I so defensive? Have I confused my core identity with the person or party I support?

The painful truth of this is, if a political leader is beyond genuine critique in your mind, the political leader has taken on a god-like status.

A large number of Christians have not wrestled through the implications of Jesus’s central teaching, The Sermon on the Mount.

One of the reasons I wrote a book on the Sermon on the Mount is because I regard this set of teachings at the most important as it relates to faithful discipleship. Jesus’s beatitudes call for a radical way of reordering the world through the upside-down nature of his kingdom value system.

To agree with someone on the political/theological left or right implies that one aligns and fully endorses that person on all matters.

We live in a day where total theological agreement determines how receptive many are to calls for compassion and mercy. Consequently, many believe that truth is not to be found in those with whom we have significant differences with. This extreme political and theological partisanship has exposed blind spots across the spectrum. The adage, “A broken clock is still right twice a day” is anathema when all of our ideological eggs are placed in the basket of our clear-eyed group.

Social media is a Power and Principality. It not only reveals, but creates environments for deception, depersonalization, and division.

In the biblical view, the powers and principalities are both invisible and visible, heavenly and earthly, spiritual and institutional. These powers are capable of taking over the lives of everyday people. This possession is manifested not through spinning heads and frightening shrieks but through the perpetuation of deception, division, and depersonalization.

The powers and principalities throughout history have been oriented around many aims, one of them being to separate us from love. Paul alluded to this in Romans 8:38–39, when he named “powers” as one of multiple spiritual influences that can seek to separate us from the love of God.

One of their characteristics in their rebellious state is to separate us from love—love of God and love for each other through deception, division, and depersonalization. Why?

Because love must be grounded in reality, nurtured in unity, and protected through the compassionate valuing of a person’s worth and dignity.

Social media undermines all of this.

Social media has great gifts to offer. Friendships have indeed been made and fostered. And there’s nothing like being wished happy birthday by numerous friends every year. But the nature of it makes transformative conversations nearly impossible. So we must be on guard.

My conversation with the heretic-shouting congregant turned out far better than I anticipated. I’m not sure if he will come back. But if he does, it gives me, and our community an opportunity to practice peacemaking. Not the kind of peacemaking that eliminates differences, but the kind that opens us up to God’s presence, and each other as well.

This is not a call to denying firmly held values. But it is a call to create environments where our disagreements don’t automatically lead to disconnection.

Dear Pastor Rich,

This is Bishop Mariann Budde. Let me begin. By saying how much your ministry has meant to me personally—particularly your writing and thoughtful engagement on social media. I also strive to stay in caring relationships with those who see the world and understand what it means to follow Jesus differently. Thank you for your witness.

This was great - eloquently written and helpful as I try to sort my feelings out about where we are going.

As a Gen Xer - I miss the days when we had to deal with people who weren’t exactly like us…. We all watched the same news, the same TV shows, we even talked to our family’s “people” (boss, friends, etc.) because we all shared one phone number.

The internet allows you to find people who are exactly like you (and then that’s where the enmeshment happens).